Knight Ridder, the second-largest newspaper publisher in America in the ’90s and videotex pioneer in the ’80s, became one of the first mainstream publishers to take its product online as AOL took off. Tony Ridder, an heir to one of the founding families and an executive on the advertising side of the business, was president of the company, working for (the now deceased) Jim Batten, a journalist who had worked his way up on the Knight side of the business. Ridder made the decision to move headquarters from Miami, Florida, to San Jose, California, and launch, along with editor Bob Ingle, a venture called Mercury Center, one of the very first online newspapers. When they began, the web wasn’t yet available so they signed on with AOL to distribute their product online.

I think that we thought it would be the newspaper in live form. Not just putting up the newspaper, but it would be the newspaper in live form, and we would offer these other services that we would have, a retrievable service so that people could access past copies of the Mercury News, and that they could search for other kinds of information.

But then Netscape came along and we could go up on the Internet. We were the first customer of Netscape. It’s interesting when you look back on it now. People are always saying, “Well, these newspaper guys never saw this coming.” I used to say, “We are not going to be a buggy whip company. We are not going to miss this wave. There’s something here, and we’re going to be part of it. We’re not going to worry about making money for some period of time. We’re going to get on top of this thing.” But even though we spent all this money….

Of course, in 2009, four years before our interview with him, Tony Ridder had stood before a gathering of employees, reportedly with tears in his eyes, to announce the sale of his namesake company to McClatchy Co. for $4.5 billion, only a fraction of what Knight Ridder had been worth just a few years before, but considerably more than it would likely be worth today.

But we are getting ahead of our story. Around the same time that AOL and other services were opening up, at least a little, to the web, strategists in the news industry grew excited that the freedom to publish directly onto the web would lead to better business models. Kathy Yates was an executive at the Mercury News and later at Knight Ridder Digital, and she recalls the clear benefits presented by the web over the proprietary walled garden services.

I just didn’t see that there was much of a future in a limited, walled garden online approach. It was just too difficult. The penetration was too thin; there was nothing about it that said to me that it would ever be a successful enterprise. The staff knew I was fairly skeptical…. One day the chief marketing officer for Mercury Center called me into the boardroom and sat me down. He said, “I’ve got to show you something.” What he showed me was, it was a beta version of Mosaic. I just…I said, “Game over. That, I believe in.”

I think what really was so striking to me about the Internet was the removal of boundaries. The newspaper business, as I experienced it, was always full of boundaries. It was very limited in so many ways. The manufacturing process. The distribution process. The limitations on how you package the news and the advertising always seemed to be putting up constraints that we were bumping into, even though we were an extremely profitable business. I think at the time the Mercury News was number one in terms of classified lineage in the country. We were always vying back and forth with The Dallas Morning News, but I think at that point we were on top.

The Internet was just so gloriously, really free, of those constraints. That’s what convinced me: “OK, this is a game changer.” From that point on I really dedicated everything to it. I signed on to become one of the founders of Knight Ridder Digital…Tony was looking to see if the experiment could be extended throughout Knight Ridder as an entire company…. That’s really how I spent the remainder of my career with Knight Ridder.

In virtually every media company, early adopters emerged, and they jumped on the prospects of the Internet with enthusiasm. One was Steve Newhouse, part of the media conglomerate that carried his family’s name, and he helped to push the business to experiment with digital technology, inspired in large part by work he saw at the MIT Media Lab.

I first became aware in the early ’90s when there wasn’t an Internet yet. It was called “new media.” No one quite knew what that was, but everyone was afraid of what it could be and wanted to be more familiar with it. I was editor of the Jersey Journal in Jersey City, New Jersey, and in the third generation of a family business. And so because no one else in the business really cared or wanted to pursue new media, I elected myself.

I joined a consortium at MIT, “News In the Future,” which was a really pioneering effort by Nick Negroponte, who ran the Media Lab, to investigate the changing landscape and [was] remarkably accurate in its focus and prediction. I remember sitting with the grad students in the Media Lab and hearing a view of news that was digital, that was interactive, and was community based. I actually saw the Internet for the first time in the Media Lab. It was before Netscape. It was text-based. It looked like the early computer programs where you typed in equations and got an answer.

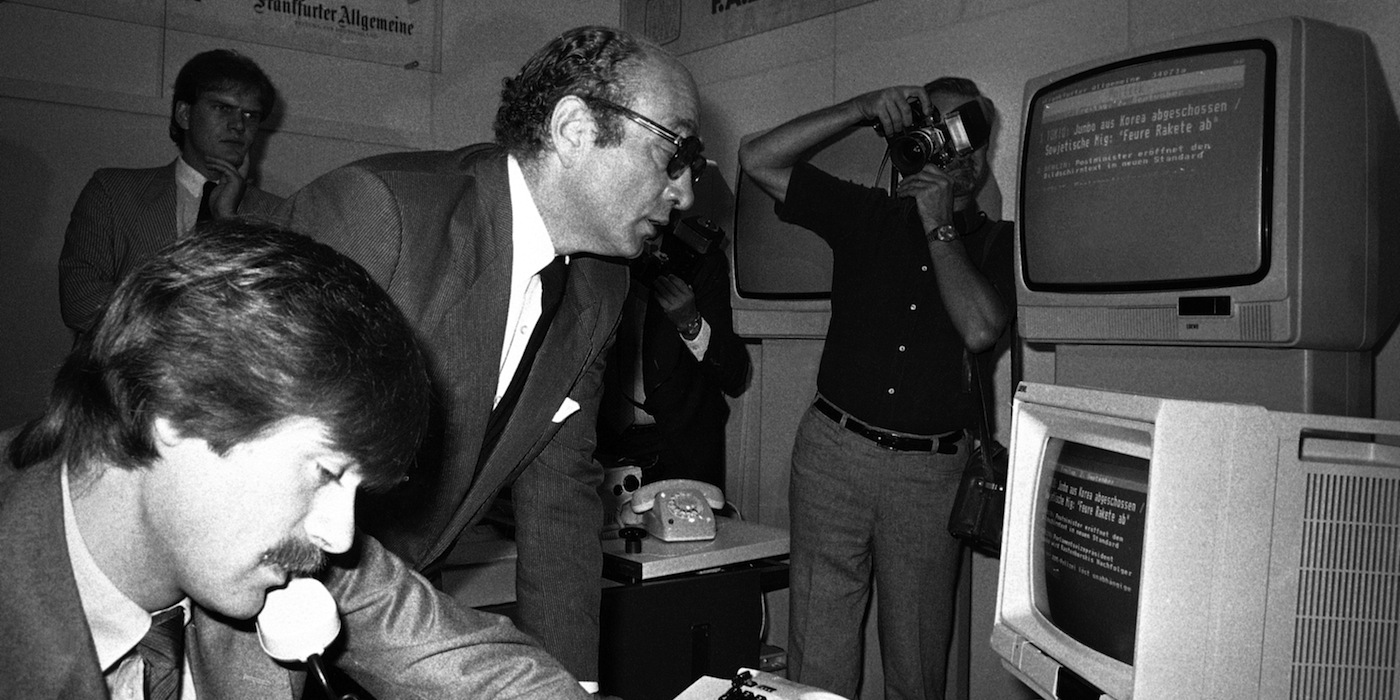

The leader of that lab was Nicholas Negroponte, who helped many established media executives get an early view of the coming digital revolution even before their companies could legally register Internet domains.

The Internet, or ARPANET, as it was called, and DARPANET, as it was called after that, wasn’t available to companies until the mid ’80s. In fact, I think it was ’87. It wasn’t legal for companies to use it. The reason I know that is that when we opened our doors for business at the Media Lab, which was October, 1985, we were fronting for companies to have email addresses because we, as an academic institution, could have them. It wasn’t quite laundering, but it allowed companies to have Internet access. We started…I believe in ’87…something called “News and the Future.”

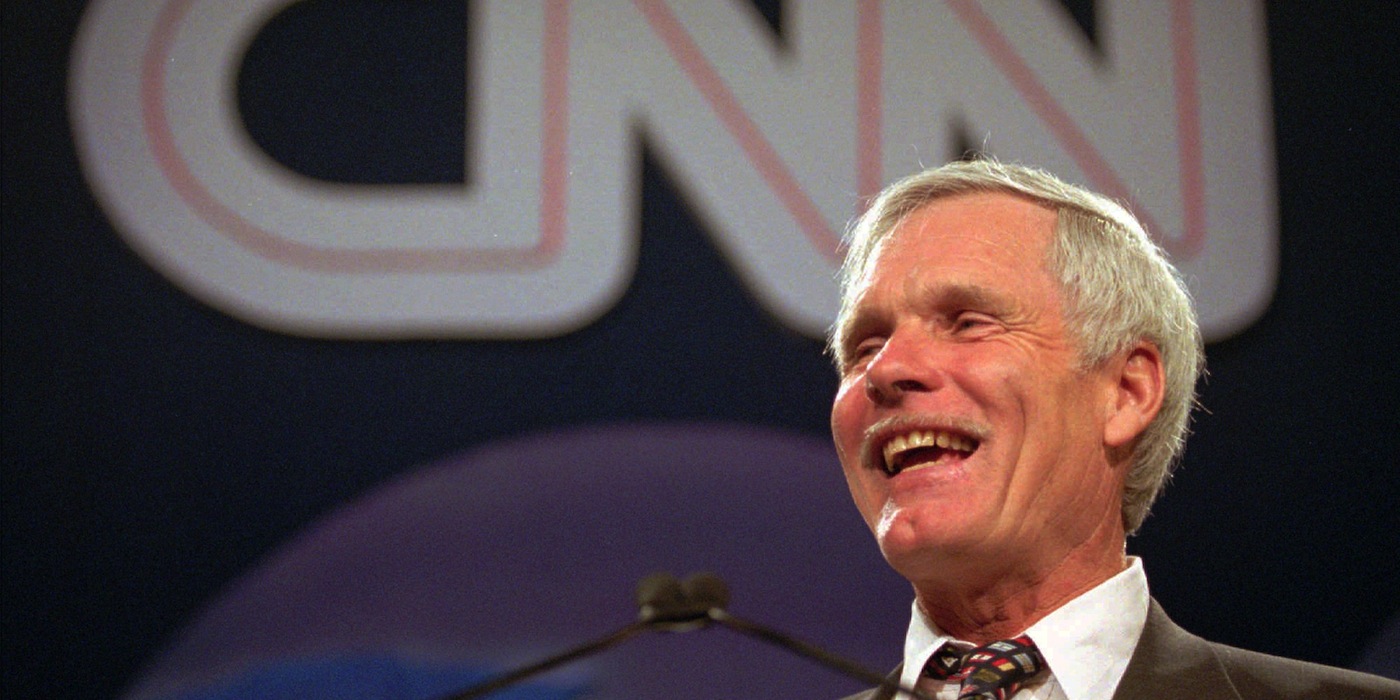

Paul Sagan

Why did you do that? What did you see?

We did that because we saw the nature of news changing very quickly. We had something called “Television of Tomorrow” that predates it by about two or three years, but that was really the technology about high definition and delivering television over telephone lines. It was very tech oriented. The “News in the Future,” we thought, would be more content oriented. We basically went to media companies and said, “You better hedge against the future and fund us.” I believe that at our peak we must have had 50 or 60 [sponsor companies].”

We had every single one of those [big media] companies as a member of “News in the Future.” The only one that was a holdout that I don’t think was ever a part of it was The New York Times. I remember in 1981 or ’82 going down to The New York Times with Jerry Wiesner [president of MIT] to see [Times executive] Sydney Gruson. Sydney and Jerry have this story they’re chatting away about. Then Sydney Gruson looks at me and says, “Young man, what is the future of newspapers?” I said, “Sir, it’s to wrap dead fish.” Jerry Wiesner never forgave me for that comment. When we did our first electronic newspaper here at the Media Lab, that was really the first web application. They named it Fish Wrap, sort of in honor of that remark.

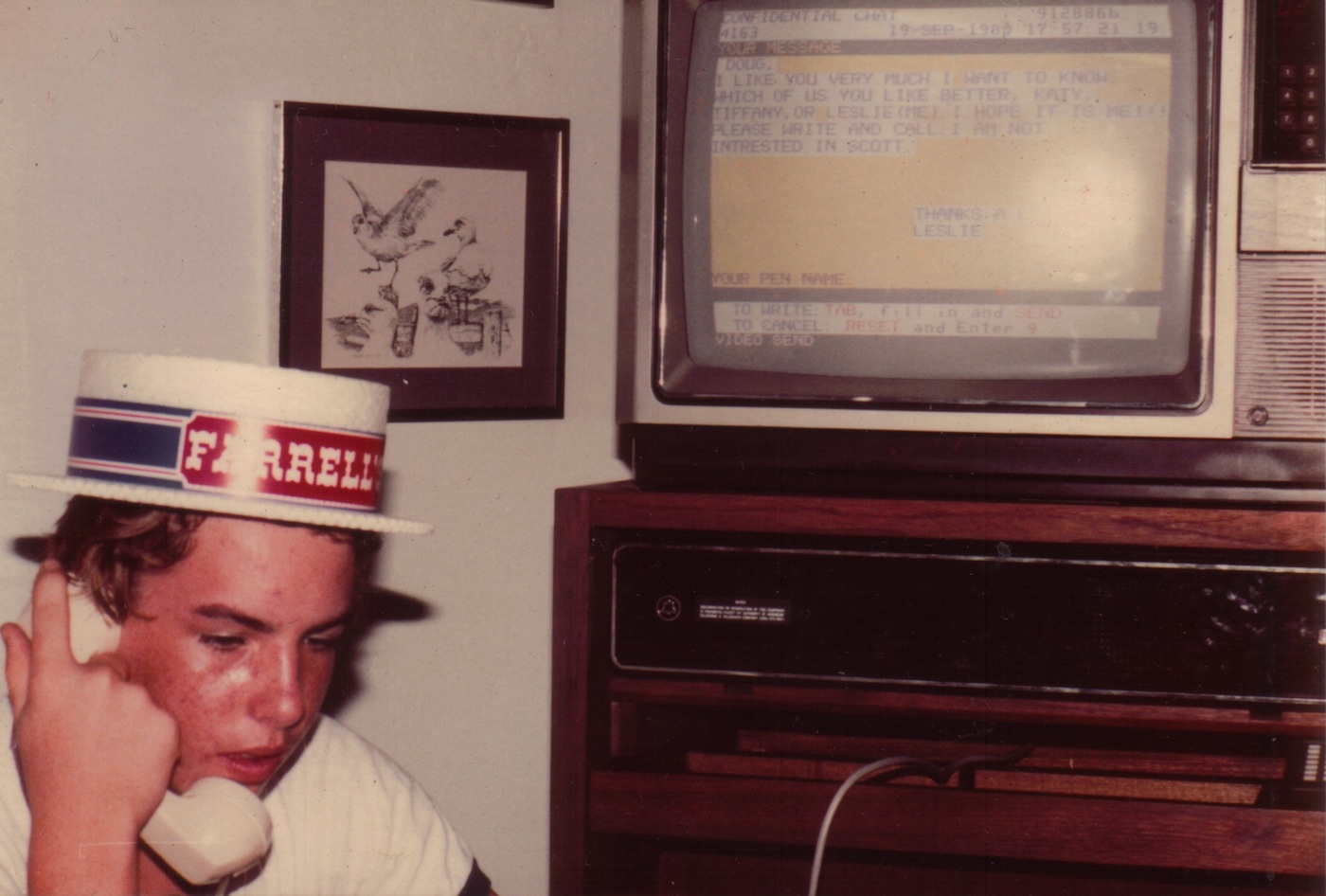

AOL founder Case remembered that in the pre-web days, even AOL was prohibited from exchanging data with the Internet because it was still not commercialized.

What’s interesting to me is that when we started in 1985, it was illegal to connect a commercial online service to the Internet. The Internet, I believe it was [until] 1991, was only for government use and university non-commercial use. Businesses could not operate on the Internet. A company like AOL could not connect to the Internet.

Our positioning in that early- to mid-1990s was AOL certainly got you access to the Internet and a whole lot more that was exclusive to AOL. That drove a lot of the growth in that 1990s period, when people were beginning to learn about the Internet. The World Wide Web was just beginning to emerge and come of age, and the way you could access that through AOL gave you a better Internet experience, plus some things that were only available if you were an AOL subscriber.

Even today, Ted Leonsis questions the conventional wisdom that the walled gardens failed because they were closed as compared to the web and the greater Internet.

We saw this other world emerging, and we were being sneered at. Remember? “You’re a walled garden. You live in the Walled Garden.” I laugh now because Apple’s the most valuable company in the world. They’re the ultimate walled garden.

And in spite of the burgeoning digerati’s condescension toward AOL as the “Internet on training wheels,” the online giant thrived in the early years when the web took the world by storm.

We started the company in 1985. We went public in 1992. It was seven years later, and we only had 200,000 customers after seven years. Seven years after that, when we were looking at, and did merge with, Time Warner, the number had gone to 20 million. But it was only the second decade when it really took off and everybody woke up to the idea of the Internet. Thankfully, at our peak, a majority of Internet usage in the U.S. flowed through the AOL systems.

Still some legacy publishers, such as Newhouse Communications, proceeded from Day One without help from the likes of AOL.

Over time, at the Media Lab, I became convinced that the Internet was the way of the future, [and we] decided to embrace it as our publishing platform. We never did a deal with CompuServe, or Prodigy, or AOL. At the same time [Nick steered us to] an unknown magazine called Wired, which had been founded in Amsterdam by Louis Rossetto and Jane Metcalfe. We made an investment in Wired.

…I became the Advance representative to Wired and would go out there [to their office in San Francisco] every couple of months and sit with Louis and Jane, and they were really pioneering people. So in the early ʼ90s we decided to start Internet sites. It was really based on the first [media company] Internet site that ever existed, which was at Wired magazine. It was called “Hotwired.”

Steve Newhouse hired New York Daily News president Jim Willse as Advance Communications’ first new media executive, and he in turn, hired Jeff Jarvis, who began planning the site that would become NJ.com — one of the first major local or regional online news efforts — as part of their effort to navigate the digital currents running across the industry.

As a sense of how early we were, we were able to sign up URLs like NJ.com, Cleveland.com, Syracuse.com because no one was doing websites with those names. Now, if I had been really smart, I would have bought a thousand of the best URLs and made hundreds of millions of dollars. But so be it. We just bought city names.

On the national side, we tried to think of how we could apply what we were seeing at Hotwired to magazines, and we decided to start a food site and build a Hotwired-like site for food because we thought looking for recipes would be a good application, which it turned out to be. That’s when we started Epicurious.

We felt that we needed to give the new medium new brands and experiment with new things. Epicurious was both a site that combined content from the two food magazines at the time, Gourmet and Bon Appetit, with a searchable recipe database and all sorts of other enhancements…that made it to the Internet. Most importantly, we believed early on in interactivity, and we allowed our users to comment on recipes, so the recipes became annotated with the comments of people who actually used them, and that became very popular.

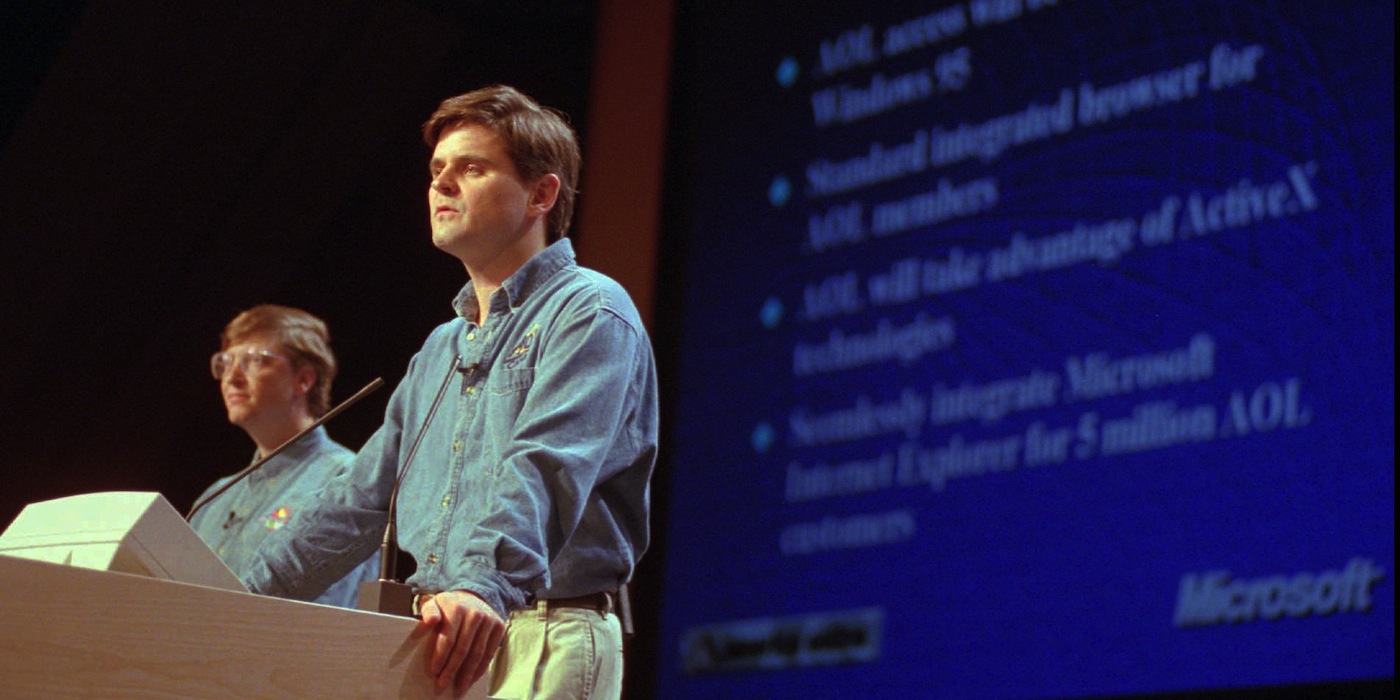

Certainly, the newspaper companies like Knight Ridder and Newhouse weren’t the only publishers taking an active interest in moving content online. At Time Inc., the largest magazine publisher in the country, interest in digitizing the titles actually arose from the journalism ranks. Walter Isaacson, soon joined by Paul Sagan from Time Warner’s cable division, worked with a small team to bring news from titles as diverse as Time, Fortune, People, and Sports Illustrated initially to the proprietary services and soon after to the web.

John Huey

Walter, can you conjure for us your first time? When the light bulb went off over your head and you said, “Ah, this digital technology in journalism is going to really change the way this all works?

Yeah. It was on a New Year’s Eve [1992], after we’d come back from a party, and Phil Elmer DeWitt had been pitching a story called “Cyberspace,” what’s happening online, digital media. I was back-of-the-book editor at Time, and late that night I went online to the Well, which was one of the early bulletin board systems that Phil had told me to go on. Totally dial-up. It was complicated because we didn’t even have dial-up modems. I had to borrow a dial-up modem. It was like 2,400 baud or whatever.

I noticed hundreds of people in these bulletin boards and sort of chat rooms. They weren’t live chat, but it was close, talking about New Year’s Eve and talking about the year, and [I was] thinking, “Whoa, there’s this whole cyber community.”

We ended up three or four weeks later using the people from Mondo 2000 — which was an early pre-Wired magazine…about the digital age — [to produce a cover for Time]. We even had hypertext, which was…the web had not flowered. There were no Mosaic browsers yet. But hypertext was still being used. And so we ran the story and some words were underlined, or in red, and they would point to things in the margin that would explain it.

After that we said, “Why don’t we put our own magazines online,” and I asked Phil. We started playing off AOL, CompuServe, and Prodigy because this is before Mosaic had made the web very accessible. If you put it up with AOL or CompuServe it had to be their subscribers. They would get revenue by the fact that the longer somebody stayed online with them the more they would pay those companies, and we would get a cut of those revenues with approximately a million dollar guarantee [from AOL].

At that magazine conference in 1993 I remember being with Louis Rossetto, who had just launched Wired magazine [and we talked about this]. But then Louis and I talked a year or so later, and we said, “Why don’t we put it directly on the Internet?” as opposed to one of these online services that were walled gardens. We made those deals with AOL, Prodigy, and CompuServe without much corporate knowledge or interference until it got to be about a million dollars of revenue a year, at which point they were paying attention. Then we had to pitch them, “Can we cut out these online services?” which wasn’t a good idea because the online services were giving us money, but it was an inevitable idea.

Every now and then we’d go up to Reg Brack, who was then president of Time Inc. He would say, “Well, who owns the Internet?” and things like that.

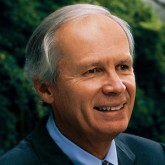

For an early adopter of digital technology, like Time Warner CEO Jerry Levin, the advent of the web seemed to offer a promising way to bring together a unified strategy for creating content, distributing it, and making money.

[Walter] came into my office and said, “There’s something called the World Wide Web. You ought to take a look at it.” It showed that somebody had finally figured out a unification strategy…. Somebody brought an agreed-upon standard so that all parties could have access to signing on and getting something back. That there was a universal code. I thought that was transformative.

John Huey

When you go back and look at the development of all this, you look at all the decisions that were made and all the coming together you described, of trying to juggle technological development with content development…Is where we are today pretty much where we would’ve ended up, inevitably, no matter what, or were there things…I’m not just talking about Time Warner, I’m talking about the whole landscape. Is there another path that, had it been taken, things would be profoundly different today? In other words, is the march of this technological disruption inevitable to all the business models, or were there other ways to have ridden the disruption that would have ended up in a profoundly different place?

I think we’re where we were meant to end up. The disruption was simply the notion of a network that has no central control that can deliver near infinite capacity. And everybody tries to figure out how to make money and what to deliver over that network. That’s where we’ve ended up. Everything pointed to that. No one owns it. I think it’s a beautiful thing.

Paul Sagan

There have been disruptive technologies in the past. Print, movies, radio, and TV. But they all accommodated each other. They didn’t kill each other. Then something happened with interactivity when we got to a public standard, or the web standard. It really started to not just make room at the table but really hurt the old distribution. Was this disaggregation or digitization? What was it that made it disruptive, as opposed to incremental?

Because it made the old form of distribution totally irrelevant. There was zero need. At least I can still go to a movie theater. There’s some socialization. Popcorn. Booze. But music, the fact that you had to buy music on a disk or listen to it on the radio…And now you can get any piece of music at all, anytime, anywhere. Why do I need anything else? This is why it’s slowly going to take the networks down. I can get online and get anything I want.

Paul Sagan

Same for journalism?

Yeah.

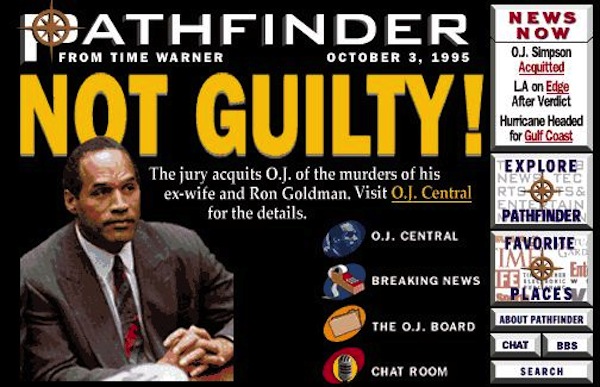

As a result of this early online experimentation at Time Warner, and with Levin’s support and encouragement, Isaacson and Sagan began working on two new media projects. One was a narrowband web service that pulled magazine content and other features together in a sort of digital newsstand they called Pathfinder. At one time it was one of the most visited sites on the web. Today it’s a single page that points from pathfinder.com to the homepages of the company’s magazine sites. The other sought to combine the broadband potential of the modern cable TV plant with direct connectivity to the public and now-commercialized Internet in a service that would come to be known as Roadrunner, named for the speedy cartoon character from the Warner Bros. stable.

It worked pretty well. We created something called Pathfinder in ’94. It was like some of the aggregators, like The Huffington Post, in a way. But it was Time magazine, Sports Illustrated, and People. It was all on a homepage. Once people got on the web, [though], they didn’t need people to package things for them. They’d do whatever they wanted.

Paul Sagan

That’s right. We arguably created the first portal. We looked at the ones that developed around search, which were really guides. We were wrong. We kept saying, “We could build a guide, too.” We looked at Yahoo and said, “We could do that, too.”

But even before Yahoo was a dream, there was some kid somewhere who started doing “my favorite websites.” It would be sports. It would be art museums or whatever. We said, “That’s how it’s going to work.” It’s going to be a directory service. That’s how you’ll find things on the web. You’ll go to a directory and find it. We did not think that kids at Stanford like Larry Page and Sergey Brin or Yahoo or whatever would create an ability to search the web well. There was a phrase back then that “content is king.” And we actually believed it.

Pathfinder was good for what it was, which was a portal. It was a place you landed on if you went right to it. We had always believed that what we were going to do was bring people into this portal. Then, when they got the content, they would subscribe to it. They would pay for it, just as you paid for any other service or magazine or subscription you had. We had an elaborate scheme for charging people, almost like The New York Times is doing now. You got a little bit for free, but then at a certain point a paywall hit.

But I remember vividly the day in mid-1994 or so when Bruce Judson (who worked on the business side of Pathfinder) came up with the concept of a banner ad. Yeah, Wired did it as well, but it was like the microchip being invented in two places at once.

Paul Sagan

It was literally one day apart.

It wasn’t the hardest concept in the world, which is, “Let’s put a banner ad on top,”…but it drove a lot of the whole shape of the business for a long time.

It really transformed everything. Immediately, Madison Avenue decided, “Oh my God, we’ve got to understand this. We have to hire a lot of young people. They would send us money. It was almost like you could look out of the Time Life Building to Madison Avenue and watch people walking with bags of money to dump it on our desk, or Bruce Judson’s desk, to buy banner ads because they all wanted to be in on this thing. What this does is, it taught us we shouldn’t charge for content. We should just get as many eyeballs as possible. That’s the way we’re going to make money. By aggregating eyeballs.

Recent Comments