“Justice League of America” was what they’d call themselves.

In October of 1999 while covering a conference in Scottsdale, eight of America’s top technology reporters – from Time, Newsweek, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Wired – agreed on a plan that a pair of them hatched. They’d quit their jobs and using their collective smarts, contacts and connections they’d build the world’s premier site covering the digitalization of people and products.

That evening, a leading venture capitalist, bumped into at the Phoenician resort’s bar, presented them a multi-million dollar term-sheet written on a napkin. By the next morning the reporters’ abandoned their dream.

Our grand plan rapidly unraveled in the light of day, of course, as most of the group realized they had incredibly great jobs and didn’t want to mess with that.

… the timing was wrong. I have a napkin where I was promised $10 million for it. I don’t know why. It just wasn’t the time. I was ready to go, but they [the other reporters] weren’t [even] a little bit [interested].

Now only one member of the Justice League remains at what was then “a major media company.” The rest are at startups.

As digital disruption buffeted and transformed media over the past quarter- century, there was one group paid to stand close and yet be apart. These were the reporters and commentators assigned to cover the technology industry, its evolution, its reach and its products. Interviews with 20 of them in fall 2014 paint a pointillist landscape of a transformative, tumultuous era.

They were charged by their bosses to be the telescopes closely tracking the tech meteor streaking through the heavens. That the rock would crash into the news business is something many of them – though not all – say they saw coming. Their predictions, they feel, went largely unheard including in their workplaces.

…That’s what the journalism business was like. We watched it, everybody saw it happening and the people who were covering it would go to their bosses and say, “We’re screwed. We’re not doing this correctly.”

No one wanted to hear what technology reporters had to say, no one….I had a good relationship with Donny Graham. He never sent stuff down to me and said, “What should we do, Steven?”

What you see depends on where you stand, and these reporters realize they’re on one of the journalism beach’s few stretches that hasn’t yet been washed away by the digital wave. Many began when tech coverage was “back of the book,” a few columns in the business pages. Since then they’ve seen a huge influx of money and talent, begetting conferences, special sections and websites that provide critical revenue lifeblood for media companies in precarious health.

You go to a Facebook announcement, and there are maybe several hundred journalists. You think “Is this industry dying or is this growing?” If you go to City Hall, or you walk into any newsroom, any metro newsroom in this country, you’re like, “What happened here? Where are the people?”

They count themselves lucky to have been witnesses. They feel they did a “pretty good” job covering this era and what it wrought. Having traveled in the same circles for years, they aren’t above talking out-of-school, exchanging bits of trash-talk and being garrulous, rather than close-mouthed, about their journey.

Most tellingly, almost all remain optimistic about the future of journalism in the digital age even if they shy from concrete forecasts and are flummoxed how their successors will earn salaries akin to what they’ve been paid.

You have to be cynical, yet optimistic about journalism. There’s a holy church of journalism, which isn’t doing that well, but there is, if you like, the faith, or the religion of journalism, which is searching for the truth. That still exists, and it will persist.

Do I feel optimistic? I’m not sure that – You’re not going to have a career in the way that you might have had in the ’70s or ’80s – or ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, which were the real boom times for it. But it’s an incredible field to be going into right now.

None discount risks ahead. Technology companies providing direct financing for those covering them can erode needed journalistic distance. Time once spent reporting may now need to be spent engaging social audiences. And reporters, under pressure to become “brands,” may need to devote time to self-promotion.

It is a new calculus, far more complex than the past occupational arithmetic based on column inches or minutes on air.

The Beginnings

The group’s educational pedigrees range from high school diplomas to Ivy League degrees. About half of these reporters who covered the early days of tech always knew they wanted to be writers, with the others stumbling into it by accident or coincidence.

A few found the door to the new career opened easily, but more were forced to make opportunistic use of whatever entry ramps were available – switchboard operator, fact checker, copy editor or angry phone-caller to editors. No one’s footsteps quite followed anyone else’s.

The editor of this paper and I had become halfway friends, and we were just talking about nothing much. At one point after having had a couple of beers I said to him something to the effect of how crappy the music reviews were in his newspaper. They were obviously with few exceptions being written by people who had no clue how music was done (and you’re way ahead of me.) He turns to me and says, “OK, asshole. You do one.” That’s how I became a journalist.

It was a strange stagger through all kinds of weird life experiences – growing up on the South Side of Chicago, going to college at Knox College, in Galesburg, Illinois, where I majored in economics. Not knowing what I wanted to do and actually working for years at the Post Office, just trying to find myself, which is a pretty weird place to do it.

All their paths crossed covering tech.

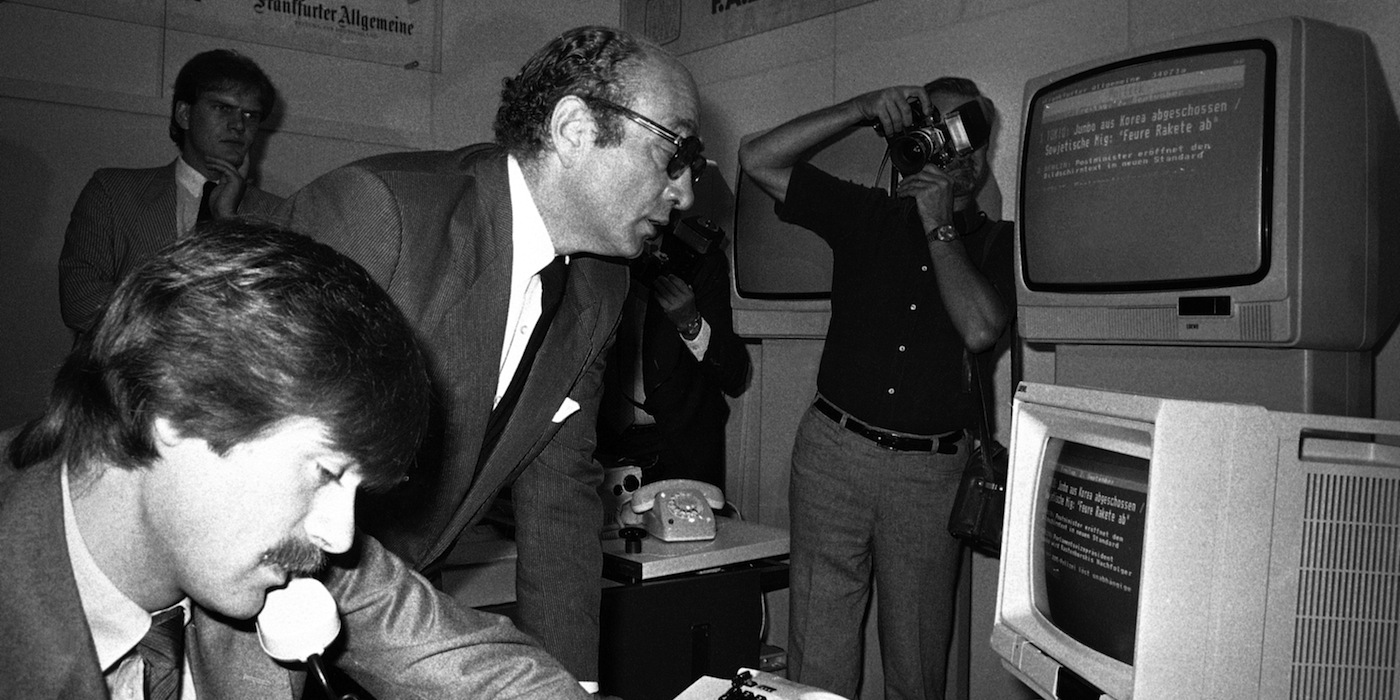

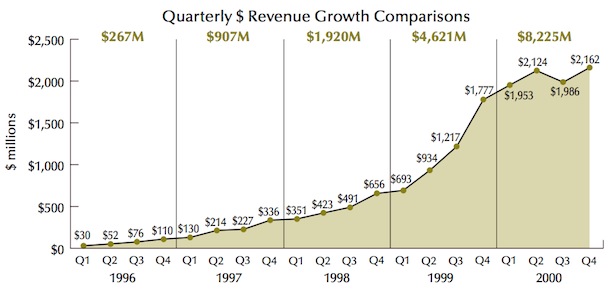

For almost 30 years after Byte magazine launched in 1975, technology and its ads became a major revenue source for magazine publishers. Bill Ziff’s Ziff-Davis and Pat McGovern’s IDG Communications battled for dominance by launching new magazines with stunning regularity. By 1989, by one accounting, IDG alone had launched 170 publications over the previous two decades, or an average of one every two months.

As Harry McCracken noted in Time last year, computer magazines at their peak were some of the greatest success stories publishing ever saw. The first issue of PCWorld in 1983 was the fattest debut issue of any magazine up until that date. PC Magazine, a competitor and ultimately top dog, was at one time listed in the top ten magazines by revenue. Computer Shopper ran more than a thousand pages in some issues. Only PCWorld remains as a print publication.

That growth led to waves of hiring. Other news organizations, seeing the booming consumer interest and advertising revenue, turned their attention and reporting manpower toward tech as well. The media lighthouse that for a century had serially cast a spotlight on steel, on railroads and then autos, found a new focus.

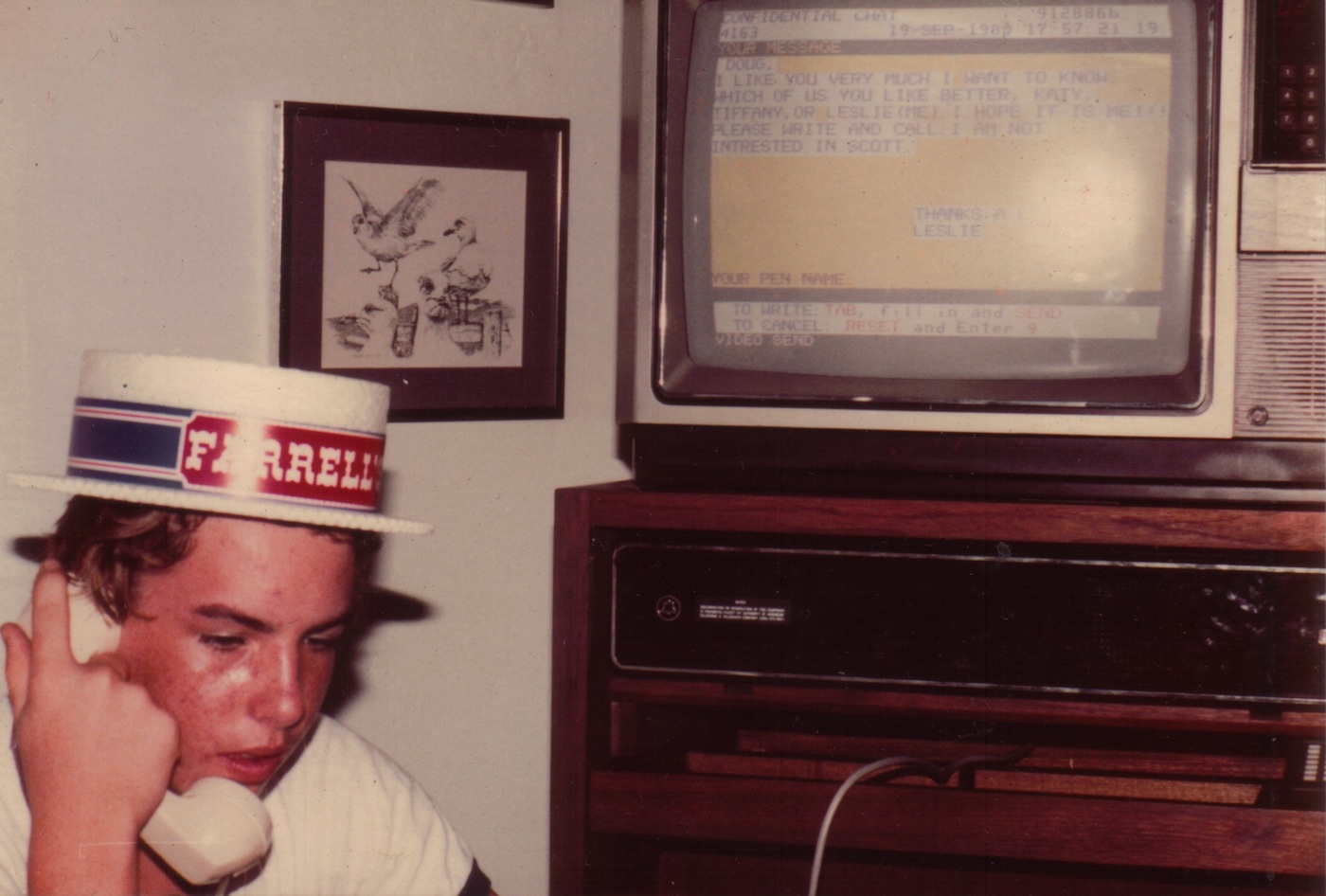

Among the first generation of reporters who gravitated toward tech coverage, a number came with a predisposition to find this new beat engaging. Some lived in northern California and had friends and neighbors getting involved in digital’s early days. Others were hobbyists and taught themselves to program early on. But tech hadn’t yet taken hold of everyone, even in San Francisco.

In the ’80s, if you were at a party and you told people that you wrote about technology for a living, it was like you dropped a stink bomb in the room. They cleared out. Nobody knew what you were talking about. They didn’t want to know what you were talking about. Like, “Oh, look at the time!” So we talked to each other.

What they talked about in this small club was their curiosity, their sense that “something’s going on here.” It tied them together whether they were at the trade press, regional newspapers or among the tiny group of reporters that national newspapers had dispatched to keep an eye open.

By their own accounts, collegiality marked their work just as much as competition. Sure, they were pressured to get scoops but the reality was that their competitive environment was shaped in part by a hierarchy that the tech companies sought to reinforce – national print outlets, then strong regional players (like the San Jose Mercury News) and then trade publications and consumer magazines.

But in the early years the technology industry wasn’t what it would become.

We would do lunch together, every week. Once a month, the tech journalists would have lunch. Steve Levy, I think you talked to him, was one of eight or 10 people. That was the entire New York tech crowd. Now, I swear there are 100 people writing just about Apple.

Because it’s a farming community, the tech business. Everybody knows everything. They all know each other, and they all chitchat amongst themselves.

Covering Technology

Historic transitions don’t happen overnight.

Railroads need tracks built. Light bulbs require an electric grid. Cars have to have gas stations. The digital era is no different. Microprocessors, computing and connectivity had to come together to ensure that the escalator effect of Moore’s Law could take hold and compound. It took a progression of events and inventions that unfolded over time, to create the breadth of the digital transformation.

When I first started writing about this in The Atlantic in the early ’80s. It was as if I was describing travel to Burma…..Most people didn’t know anything about it. You’re in the role of the classic middle man, going from a realm where people had expert knowledge, and you’re conveying that to people.

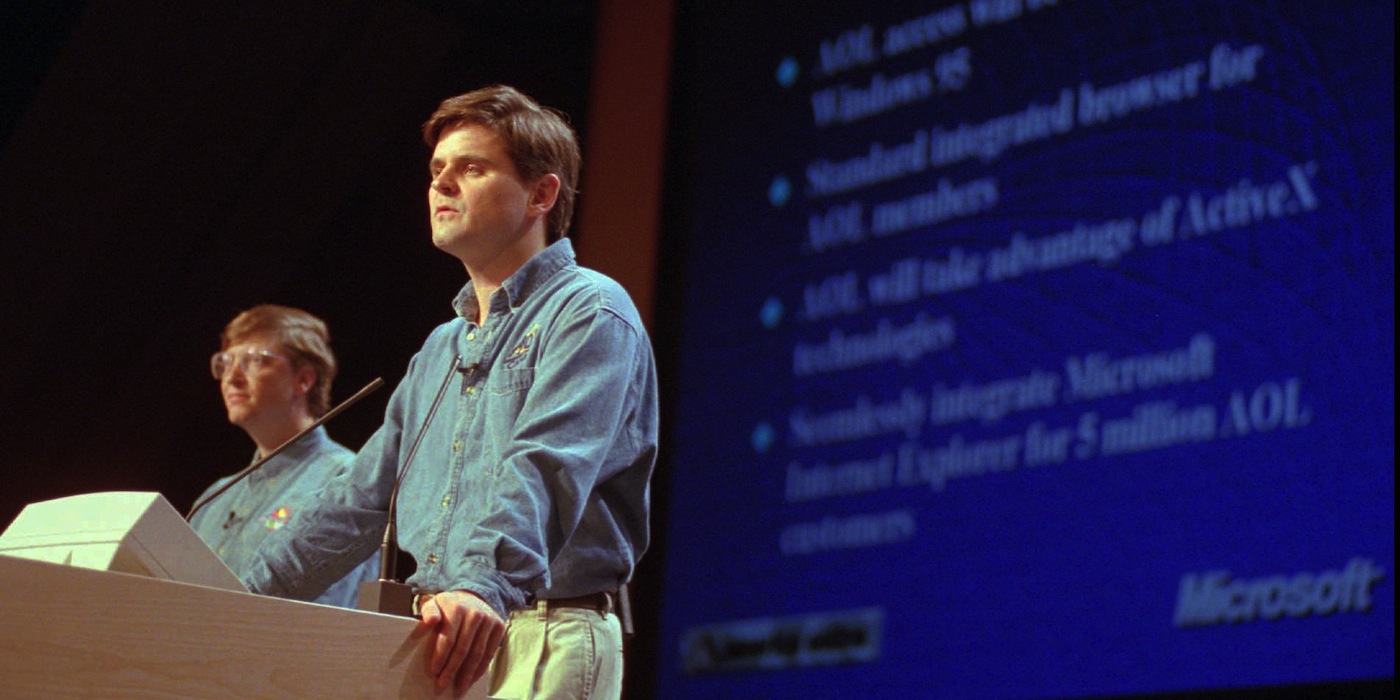

But, as Fallows says, the mainstreaming of once obscure knowledge into something essential forced change. A world populated by computer clubs, renegade hackers and garage offices began, in fits and starts, to turn into one dominated by huge digital ecosystems – Apple, Microsoft, Google, Facebook – where each platform saw market dominance as the best path to growth and financial success.

Those transitions changed how journalism was practiced as well. The way they covered the industry and their access to sources evolved from somewhat relaxed with fairly easy accessibility, into the more disciplined model familiar in other industries.

Well of course, in a lot of ways it was easier for us in the early days… easier for us to get closer, to get a unique story, but harder to get information probably, because information just wasn’t flowing out everywhere. You had to really use your reporting skills and your interpersonal skills to get information.

I was very lucky too, in that I worked at a time when people who were really significant only had to deal with maybe a half a dozen publications. If you could build a good relationship with one of these key people, it would pay off in much better stories and you build trust, you build a personal relationship

You could talk to these executives directly. They had PR people. But it was a different time, where I was also young and so I would go out drinking with the same people who I covered in a way that I had no access to [when I worked in Washington] with congressmen that I wrote about. I imagine that was a unique moment in time. It’s very different now. But it was a really lovely time.

What has also evolved is a model similar to Hollywood or Washington or any locale where “pack journalism” exists, as reporters seek ways to cover influence or wealth or power. Access becomes critical and it can become a currency to be traded.

The more access you have, the less willing you are to write something negative, and [risk] losing the access. I know that certainly is endemic here in Washington with political reporters. I don’t know for sure, but I can see the same thing happening in tech.

If you’re well known in your own right, the issues of access are stable no matter what. The only thing that would be different is if you have partnerships and relationships business-wise with some of these places there. It wasn’t so much Newsweek, but at Wired I was constantly being called on to bring in my sources for speaking events. I never was all that happy about that, because I always feel that you have a certain amount of capital with these people. I prefer to use my capital to get stories rather than conference appearances.

These issues are readily discussed, even if not easily solved. Disclosure is often advocated as a tool to control the ethical risk but it sometimes may leave onlookers unnerved at the amount of overlap between those being covered and those doing the covering.

Impact

Many of these reporters gained their own Aha! or Eureka! moments covering technology, those sudden epiphanies when they realize that tomorrow will be different then today.

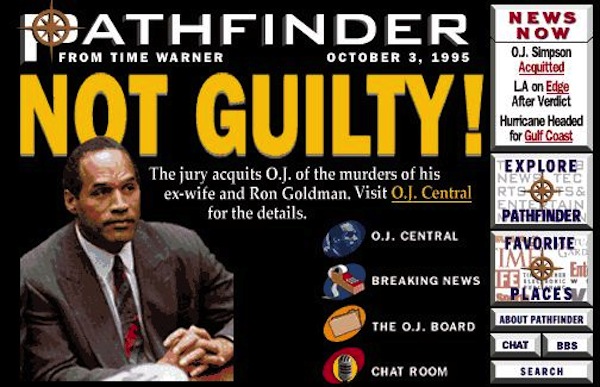

Many mention the introduction of PCs, the Internet, the Mozilla browser and Apple’s products and networking. Other touchstones range from being able to measure the worldwide thirst for news on 9/11 to Wikileaks demonstrating the virality of secrets unveiled.

People knew it was going to be the Year of the Network. We used to joke about this. It was the Year of the Network every year for like 15 years, before it was finally the Year of the Network . Those two things [computing and connectivity] had to happen, before you could really see where things were going.

I remember two products that gave me chills. One was when Steve Jobs first held up the iPhone. I’m like, “That thing has no buttons and no keys. What is he thinking?” Man, they saw so far out that day when they showed the iPhone. That really has changed everything. I mean everything! The touchscreen smart phone…I mean it’s now, who buys radios anymore? Who buys cameras anymore? Who buys newspapers anymore? It’s all there.

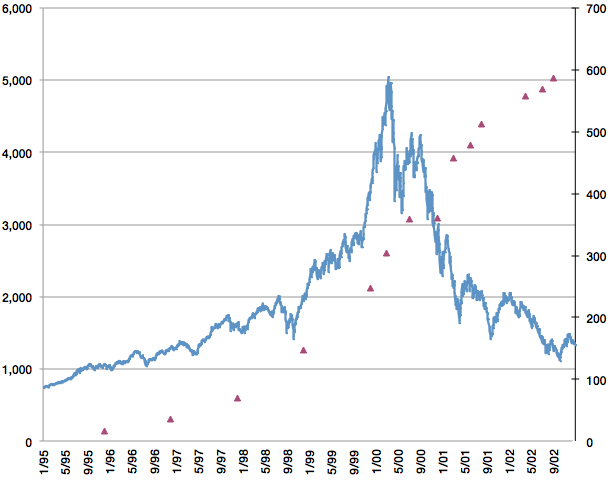

Among these interviewees, there is a broad, although not unanimous, belief that by the mid-1990s it was clear that the news business was going to have to change fundamentally. They say they sounded alarms. They cite their own stories, discussions at industry meetings and other forums as evidence that the industry was told, but didn’t hear. Or didn’t want to hear.

I thought, “We are in huge trouble.” I started stomping around at all the journalism conferences saying, “You have got to pay attention to this,” and nobody wanted to listen. In fact, at one conference – I shouldn’t name who it is; he would be so embarrassed – someone, a very august person, at a very well known publication, stood up and put his fingers in his ears and said, “La, la, la, I can’t hear you. I don’t want to hear this. I don’t want to hear it.”

A minority say they didn’t see the disruption coming to the news media. Some cite their natural optimism, others their professional skepticism or simply say that they were working too hard on day-to-day coverage of the technology industry to lift their heads and see what was coming toward them.

I didn’t understand, actually, that the very things that I embraced – blogging and online communication and stuff – was basically going to destroy the industry that employed me, and that pretty soon I was going to feel like a mid-level manager at the buggy whip factory several years into the introduction of cars.

They say the news business’ failure to act was due to inertia, an unwillingness to endanger their existing business revenue and, to some, the fact that journalists, rather than engineers, were leading many of the companies.

I think big media companies tend to be risk-averse. I just do. Particularly the ones that have achieved a lot of influence and power, whether it’s The New York Times Company or Dow Jones and The Wall Street Journal or it’s, I don’t know, Condé Nast or Hearst or it’s the television network companies, whatever.

There’s also another interesting thing about journalists: there is real arrogance about what was going on. There was a real head-in-the-sand mentality. Kind of what you said worked, “This thing is going to go away. This is stupid. I want to go back to what I want to do, because what they’re doing is pure and what you’re doing is not pure. We don’t chase the money. We don’t care about that. We’re just going to stay here. We’re going to keep doing this until the bitter end.” That’s exactly what they got.

Corporate entities in general are very slow to recognize, to exploit, to understand the new technologies. It’s not just the old media. It’s goods and service companies of every size and shape. When you are a successful company, you’ve been doing things a certain way and that’s what made you successful. It would take a very unusual person or leadership to say what we should do now is abandon what’s made us successful and try something unproven.

Also seen contributing to the slow response was the news media’s relationship with its audience. When many of these reporters began, readers were only heard from rarely. Audience measurements were sporadic and imprecise. Writers never knew whether readers read a story in whole, in part, or if at all.

This ignorance provided insulation and distance, which Kara Swisher says was the curse of the business. “They didn’t care to talk to readers…They liked their little worlds they had built, where they talked down to people, where there was no back and forth.”

The advent of email, social media feeds and easily attainable user metrics has toppled any hint of a belief that readership would remain at a distance. But responding to that readership has also changed the equation about how a journalist divides up the day – reporting or outreach or promotion.

I don’t feel like I’ve gotten there yet, in some ways. I tweet. I follow people, I retweet, but I think the way to do it I’m not there yet… It’s not because I’m against it. I think it’s great. It’s just a time factor for me.

There’s been another change as well. Journalism always had stars, whether they were movie or book reviewers, columnists, political insiders or sometimes just veteran reporters. But the stars were mostly fixed in a single galaxy anchored by a newspaper, a television network or a magazine. They rarely moved.

There was a compact, sometimes entered grudgingly, between a media institution and the individual. The institution argued that its standards and reputation helped lift individuals so that readers could find them (but the stars should not outshine the galaxy). The stars – lacking their own printing presses, trucks or antennas – seldom had an opportunity to prove their independent strength.

But people become institutions in a way that they didn’t used to. I mean, that’s one of the fundamental things of the Internet.

They always made publishers uncomfortable. It was a two-edged sword. It helped the paper, because they had followings. This is a really important word, followings… There always were stars. I think what makes it a brand is the web.

Today, publications that allow their reporters to become their own brand, I think, are doing themselves a service. I know some reporters don’t want to do that or don’t know how to do that, but I think, again, it goes back to creating those relationships and creating that name for yourself out there in cyberspace. People are drawn to that because there’s so much out there, that the brand of the reporter then becomes the filter. They may not like the publication, or they may not like this or that, but they can trust the reporter.

A, B, C, D, or F

Grading yourself is never easy.

Asking these journalists how they think their craft has done covering the digital evolution of the last thirty years gets a range of answers. Using different individual yardsticks, they variously give the craft a C+ or so, with a few graders pushing the group higher on the curve.

I’d give them a “C”. They’ve missed huge things, and people who believed what they are writing made huge mistakes.

There’s a golden age and I believe it was from 1987 to about 1997. Maybe a decade. That was when everything was popping. Everybody was doing well and there were experts that were explaining what was going on and they did a good job of it….[after that] it was a slow degradation of tech reporting into gizmos, too many gizmos and gadgets.

We’ve done OK. I wouldn’t say it’s an A. I would say maybe a B, maybe a C. The reason I say that is that there’s a lot of shiny coverage and there’s an occasional deep dive.

By and large, the technological journalist corps that you’re looking at has not been an adversarial group. They haven’t told the hard stories well enough, I think. Part of that, I’m critical of myself…

James Fallows eschews grades altogether. He argues that the best tool might be one he uses when he travels. If after reading about some locale in the press, you arrive and find things fundamentally different from what you’ve been led to expect, journalism has failed.

Most people know about Moore’s Law. Most people have a sense of some of the ripple implications. The science sections in The Times and other papers have done a good job. Most people know all the business drama. I think this is something that in terms of an ongoing revolution, journalism has done OK, I think.

Are there recurring weaknesses? There are many cited. Among those cited are “cheerleading” as the newest gadget gets disproportionate coverage, outsized competition for tiny scoops rather than more probing inquiries and a certain lack of nuts-and-bolt coverage of how these firms do business.

Split Future: Journalism and the News Business

No one interviewed claims to know what might be a next, more lasting iteration of the news business.

While a handful have left journalism behind, the rest are still practicing their craft. Most are no longer with their old employers, but have instead struck out with new owners to test new platforms, tactics and approaches in the hope that one may prove durable.

Some of the ventures are backed by deep-pocketed investors with Silicon Valley connections, others are relying on investments from big media companies trying new tactics (Yahoo, Medium, NBC) and some are funded philanthropically (ProPublica). All of them have hopes. None see the future as assured.

“The purposes and the coverage areas and the financial models have all split this thing apart,” Esther Dyson says of the news business. She believes business journalism may provide one path because accuracy is worth a monetary premium. “A premium about the philosophical, ontological state of the world? It’s harder to get people to pay for that, partly because everybody’s competing to provide this for free.”

Among the interviewees there is broad agreement that there won’t be one business model but a variety based on what’s being covered and for whom. Niche interests and audiences may gain loyalty and a following willing to subscribe. There may be a broader audience and advertising revenue for celebrity coverage, sports or humor. As for public service journalism, that’s where philanthropy and wealthy backers play a role.

It makes me very nervous. This is one of the things that has happened as our revenue model has been ravaged. Don’t misunderstand me. This whole concept of “objective” journalism is just a tradition. There is nothing in principle wrong with newspapers having a slant, as long as you know what it is. But you want to be careful when people are presenting as objective journalism stuff that may have been subsidized by people with a dog in the fight.

One of the interesting things that’s happened even in the time I’ve been here is a mindset that’s gone from “journalism has to be profitable to be successful” to “good journalism is probably going to struggle to be profitable, so we have to find ways of supporting it.”

Somewhat counter-intuitively, a greater optimism prevails about the outlook for journalism, which they view as being distinct, if not completely separate, from the travails of the news business. They’re bullish about their craft.

Some will say they’re optimistic by nature. Others cite historic precedent (the bloom of muckraking journalism in the early 1900s) to demonstrate that truth- telling and inquiry will always find a market. And more argue that the new tools the digital age has made available for journalism will lead to a blossoming, not a withering, of public-spirited inquiry.

Journalism is already much better than it was because of the Internet and is going to be better still…I’m not only excited about the future of journalism. I’m excited about the future of humanity because of that. Knowledge, as you know being in the knowledge business, that’s the greatest thing we can give people.

I’m optimistic about journalism. I’m not optimistic about newspapers. I think it’s over…People have this romantic attachment, “Ooh, it was like…” I’m like, “You know what? It wasn’t so good for women. It wasn’t so good for blacks. It wasn’t so good for customers.” It was good for a group of people, but…and it wasn’t such good journalism, by the way. Some of it was, but boy, is more good information out there for users than ever before. I think people love great content, and smart people will find a way to do it.

I’ve been in Business Insider’s newsroom – again, desks and desks, journalists writing, working there. There’s all these other brand new newsrooms that didn’t exist before, that are hiring journalists today. The job might be a little different and the approach might be more demanding, but they’re journalists. This field isn’t dead. It’s like new institutions rising there and they’ll be just as sclerotic in their own sense in a few years, it’s just as well. Another place will come up.

A few mention a need to refocus their craft. As computers gain the ability to write police reports, cut-lines, and the like, a few see a potential to shift journalism toward fuller inquiries and more ambitious stories. Others hope that to differentiate themselves from computers, past journalistic imperatives will reawaken – the old “get out from your desk and go find sources” admonition.

None of this is to imply there aren’t risks, or that events don’t, at times, give them pause. In many of them, expressions of optimism can be followed quickly by a journalistic “yes, but” reflex. They worry about readers, how they’ll pick reliable sources of information. They worry that new publishers won’t necessarily know how to, or want to keep journalism credible. And they worry about themselves.

Will a “golden age” of journalism fade into the shadows before the new one blooms in front of them?

I just spent a year on an [Artificial Intelligence] book. Watching the pace in these automated systems and what they’re doing to intellectual work, why should journalism be protected? If you can do sports and you can do the city hall and you can do entertainment all very well by machine, what’s left? Right now, Narrative Science and a couple of other companies are taking stumbling steps, but I expect more. That forces us, as human journalists, to be more creative and maybe spend our time turning over rocks, but there might be fewer of us too.

I’m both [optimistic and pessimistic]. There’s more opportunity for people to express themselves than ever before. But, it’s harder to find an audience, a significant audience than it’s ever been before. It’s hard for established brands just to hang onto their volume. It is really splintered. I guess that means you don’t have as much power as before. That’s regrettable if you’ve had power and you’re used to it. What I worry about is we live in this winner-take-all-world now.

As far as I can tell, journalism has always had a problem of paying for reporting. What you would think of as serious reporting, whether it’s international or state house or investigative has never paid its way. It’s had to find different host bodies to latch itself onto.

Whether it was the evening tabloid 100 years ago people could read in the subway or whether it was, when I was a kid, the Los Angeles Times was 500 pages per day because it was the only real way to reach the advertising market of the southern California basin. Even my hometown was 70 miles from Los Angeles but still it was the main advertising vehicle.

That continues to change and a new host body needs to be figured out. We’re in the process of that. I think the craft of describing the world may actually be improved now. If you have a combination of professional reporters (as you can find ways to pay them with the skills they have) and real-time, opportunistic video and reportage.

Technology journalists did a good job covering the birth of the digital age. That doesn’t mean it was perfect.

Journalism has always put a premium on “what’s new.” In covering an industry undergoing historic, wrenching growth, it isn’t surprising that more reflective reporting often took a back seat. A focus on what’s coming down the road directs attention away from examining what exists today or what’s been left behind.

So gadgets probably got too much coverage. But there were articles written, many by the reporters interviewed, on the economic and societal changes wrought by the birth of the digital era. There could have been more but it is uncertain, given the nature of the change, if the news industry would’ve been any better prepared for its future.

Reporters are paid to be witnesses, not oracles. Their prognostications may sometimes be right, but their prime responsibility is to accurately describe what’s taking place. They’re meant to stand apart from the melee they’re covering.

And they stood apart too from the business operations of the companies they worked for. Media companies each had their own unique anthropologies, but reporters occupied a common position in all the corporate constellations – they were insulated from the commercial side.

This need to shield journalists from business pressures created a constant organic tension within every news organization and may have also created a hierarchy of internal stakeholders. While the entity’s survival mattered to all, the business side alone had the day-to-day commercial responsibilities. The news side was viewed as unschooled and unskilled in making business decisions.

One result may have been that the reporters’ prognostications resonated less inside these media companies than they did outside. But that may be more an anecdote from a rosy past rather that a prescription for a new future since none now profess any great insight about what a viable business model for news might be.

That missing “what next” makes the current Journalism-In-Crisis discussions different from those that have punctuated professional gatherings for the last century. Common traditional themes – professionalism, commercialism, audience and credibility – still fuel discussion, but a tangible undercurrent of uncertainty flows throughout the interviews.

There is only one bet they’re all willing to make. The news business may dissolve, but journalism won’t. Journalism that isn’t polemical, that represents a good faith effort to get to the bottom of things, is what democracies, individuals and businesses depend on to make decisions.

It will matter more in the future simply because more information demands better guides and interpreters.